Cybersleuths Uncover 5-Year Spy Operation Targeting Governments, Others

Monday, January 14, 2013 at 11:23AM

Monday, January 14, 2013 at 11:23AM

By Kim Zetter for WIRED

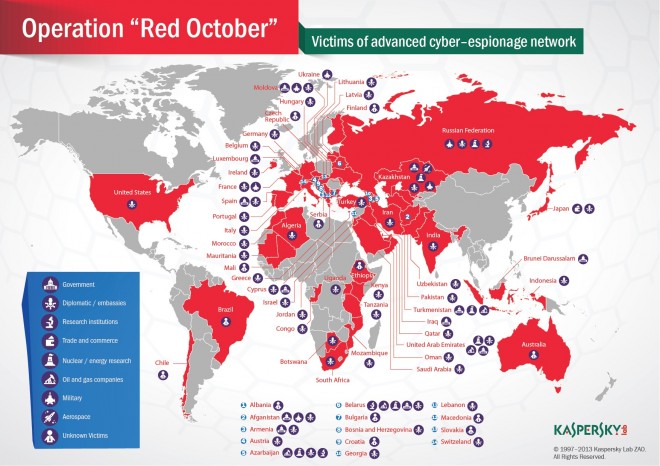

An advanced and well-orchestrated computer spy operation that targeted diplomats, governments and research institutions for at least five years has been uncovered by security researchers in Russia.

The highly targeted campaign, which focuses primarily on victims in Eastern Europe and Central Asia based on existing data, is still live, harvesting documents and data from computers, smartphones and removable storage devices, such as USB sticks, according to Kaspersky Lab, the Moscow-based antivirus firm that uncovered the campaign. Kaspersky has dubbed the operation “Red October.”

While most of the victims documented are in Eastern Europe or Central Asia, targets have been hit in 69 countries in total, including the U.S., Australia, Ireland, Switzerland, Belgium, Brazil, Spain, South Africa, Japan and the United Arab Emirates. Kaspersky calls the victims “high profile,” but declined to identify them other than to note that they’re government agencies and embassies, institutions involved in nuclear and energy research and companies in the oil and gas and aerospace industries.

“The main purpose of the operation appears to be the gathering of classified information and geopolitical intelligence, although it seems that the information-gathering scope is quite wide,” Kaspersky notes in a report released Monday. “During the past five years, the attackers collected information from hundreds of high-profile victims, although it’s unknown how the information was used.”

The attackers, believed to be native Russian-speakers, have set up an extensive and complex infrastructure consisting of a chain of at least 60 command-and-control servers that Kaspersky says rivals the massive infrastructure used by the nation-state hackers behind the Flame malware that Kaspersky discovered last year.

But the researchers note that the Red October attack has no connection to Flame, Gauss, DuQu or other sophisticated cyberspy operations Kaspersky has examined in recent years.

The attack also shows no signs yet of being the product of a nation-state and may instead be the work of cybercriminals or freelance spies looking to sell valuable intelligence to governments and others on the black market, according to Kaspersky Lab senior security researcher Costin Raiu.

The malware the attackers use is highly modular and customized for each victim, who are assigned a unique ID that is hardcoded into the malware modules they receive.

“The victim ID is basically a 20-hex digit number,” Raiu says. “But we haven’t been able to figure out any method to extract any other information from the victim ID…. They are compiling the modules right before putting them into the booby-trapped documents, which are also customized to the specific target with a lure that can be interesting to the victim. What we are talking about is a very targeted and very customized operation, and each victim is pretty much unique in what they receive.”

The statistics on countries and industries are based on Kaspersky customers who have been infected with the malware and on victim machines that contacted a Kaspersky sinkhole set up for some of the command-and-control servers.

Raiu wouldn’t say how his company came across the operation, other than to note that someone asked the lab last October to look into a spear-phishing campaign and a malicious file that accompanied it. The investigation led them to uncover more than 1,000 malicious modules the attackers used in their five-year campaign.

Sample of an image that appeared in a phishing attack sent to a “Red October” diplomatic victim. Courtesy of Kaspersky Lab

Each module is designed to perform various tasks — extract passwords, steal browser history, log keystrokes, take screenshots, identify and fingerprint Cisco routers and other equipment on the network, steal email from local Outlook storage or remote POP/IMAP servers, and siphon documents from the computer and from local network FTP servers. One module designed to steal files from USB devices attached to an infected machine uses a customized procedure to find and recover deleted files from the USB stick.

A separate mobile module detects when a victim connects an iPhone, Nokia or Windows phone to the computer and steals the contact list, SMS messages, call and browsing history, calendar information and any documents stored on the phone.

Based on search parameters uncovered in some of the modules, the attackers are looking for a wide variety of documents, including .pdf files, Excel spreadsheets, .csv files and, in particular, any documents with various .acid extensions. These refer to documents run through Acid Cryptofiler, an encryption program developed by the French military, which is on a list of crypto software approved for use by theEuropean Union and NATO.

Among the modules are plugins for MS Office and Adobe Reader that help the attackers re-infect a machine if any of its modules get detected and zapped by antivirus scanners. These plugins are designed to parse Office or .pdf documents that come into the computer to look for specific identifiers the attackers have embedded in them. If the plugins find an identifier in a document, they extract a payload from the document and execute it. This allows the attackers to get their malware onto a system without using an exploit.

“So even if the system is fully patched, they can still regain access to the machine by sending an email to the victim that has these persistent modules in Office or Reader,” Raiu says.

The attackers are believed to be Russian-speaking, based on registration data for many command-and-control servers used to communicate with infected machines, which were registered with Russian email addresses. Some of the servers for the command structure are also based in Russia, though others are in Germany.

In addition, researchers found Russian words in the code that indicate native speakers.

“Inside the modules they are using several Russian slang words. Such words are generally unknown to non-native Russian speakers,” Raiu says.

One of the commands in a dropper file the attackers use changes the default codepage of the machine to 1251 before installing malware on the machine. This is the code base required to render Cyrillic fonts on a machine. Raiu thinks the attackers may have wanted to change the code base in certain machines to preserve the encoding in stolen documents taken from them.

“It’s tricky to steal data with Cyrillic encoding with a program not created for Cyrillic coding,” he notes. “The encoding might be messed up. So perhaps the reason to [change the code base] is to make sure that the stolen documents, explicitly those containing Cyrillic file names and characters, are properly rendered onto the attacker’s system.”

Raiu notes, however, that all of the clues pointing to Russia could simply be red herrings planted by the attackers to throw off investigators.

Chart showing the location of infected machines that contacted Kaspersky’s sinkhole over a two-month period. Courtesy of Kaspersky Lab

Although the attackers appear to be Russian speakers, to get their malware onto systems they have been using some exploits — against Microsoft Excel and Word — that were created by Chinese hackers and have been used in other previous attacks that targeted Tibetan activists and military and energy-sector victims in Asia.

“We can assume that these exploits have been originally developed by Chinese hackers, or at least on Chinese code page computers,” Raiu says. But he notes that the malware that the exploits drop onto victim machines was created by the Red October group specifically for their own targeted attacks. “They’re using outer shells that have been used against Tibetan activists, but the malware itself does not appear to be of Chinese origin.”

The attack appears to date back to 2007, based on a May 2007 date when one of the command-and-control domains was registered. Some of the modules also appear to have been compiled in 2008. The most recent was compiled Jan. 8 this year.

Kaspersky says the campaign is much more sophisticated than other extensive spy operations exposed in recent years, such as Aurora, which targeted Google and more than two dozen other companies, or the Night Dragon attacks that targeted energy companies for four years.

“Generally speaking, the Aurora and Night Dragon campaigns used relatively simple malware to steal confidential information,” Kaspersky writes in its report. With Red October, “the attackers managed to stay in the game for over 5 years and evade detection of most antivirus products while continuing to exfiltrate what must be hundreds of Terabytes by now.”

The infection occurs in two stages and generally comes via a spear-phishing attack. The malware first installs a backdoor onto systems to establish a foothold and open a channel of communication to the command-and-control servers. From there, the attackers download any of a number of different modules to the machine.

Every version of the backdoor uncovered contained three command-and-control domains hardcoded into it. Different versions of the malware use different domains to ensure that if some of the domains are taken down, the attackers won’t lose control of all of their victims.

Once a machine is infected, it contacts one of the command-and-control servers and sends a handshake packet that contains the victim’s unique ID. Infected machines send the handshake every 15 minutes.

Some time over the next five days, reconnaissance plugins are sent down to the machine to probe and scan the system and network in order to map any other computers on the network and steal configuration data. More plugins follow later, depending on what the attackers want to do on the infected machine. Stolen data is compressed and stored in ten folders on infected machines, after which the attackers periodically send a Flash module to upload it to a command-and-control server.

The attackers steal documents during specific timeframes, with separate modules configured to collect documents across certain dates. At the end of the timeframe, a new module configured for the next timeframe is sent down.

Raiu says the command-and-control servers are set up in a chain, with three levels of proxies, to hide the location of the “mothership” and prevent investigators from tracing back to the final collection point. Somewhere, he says, lies a “super server” that automatically processes all of the stolen documents, keystrokes and screenshots, organized per unique victim ID.

“Considering there are hundreds of victims, the only possibility is that there is a huge automated infrastructure which keeps track of … all these different dates an which documents have been downloaded during which timeframe,” Raiu says.”This gives them a wide view of everything related to a single victim to manage the infection, to send more modules or determine what documents they still want to obtain.”

Of the more than 60 domains the attackers used for their command-and-control structure, Kaspersky researchers were able to sinkhole six of them beginning last November. Researchers have logged more than 55,000 connections to the sinkholes since then, coming in from infected machines at more than 250 unique IP addresses.

Reader Comments